Bitcoin is open-source; its design is public, nobody owns or controls Bitcoin and everyone can take part. - bitcoin.org

Background: the Bitcoin white paper was released under the pseudo-name Satoshi Nakamoto on 2008-10-31, poignantly this was a time when the traditional banking system was in turmoil at the onset of a global financial crisis. The identity of Author Satoshi Nakamoto is not known, with some speculating that Satoshi is actually a group rather than an individual. Satoshi circulated the Bitcoin paper on an internet mailing list for Cypherpunks, a group of activists that advocate the use of cryptography and privacy enhancing technologies as a route to social and political change. Creating a digital money independent of the traditional banking system for use on the internet had been a long term aspiration of the libertarian minded Cypherpunks. Ironically, much of the cryptography underpinning the sometimes lofty idealism of the Cypherpunk movement was developed in the 1970s within government intelligence agencies the NSA (USA) and GCHQ (UK).

Motivation: in this post I will give additional commentary on the Bitcoin white paper, as well as definitions, and links to resources. I will quote the paper verbatim in the grey boxes, and highlight text to be defined or further explained. The paper mainly describes the technical mechanisms underpinning the Bitcoin blockchain, but also touches on issues in banking, monetary policy, and incentive structures. The brilliance of the Bitcoin protocol is in the design of a system combining cryptographic techniques in a peer-to-peer network that has a concept of memory, with a self-regulating system of incentives. On first reading the paper can seem sparse and obtuse, but with sufficient context and understanding I hope to demonstrate to you its elegance, and momentous implications.

A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution. Digital signatures provide part of the solution, but the main benefits are lost if a trusted third party is still required to prevent double-spending. We propose a solution to the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer network. The network timestamps transactions by hashing them into an ongoing chain of hash-based proof-of-work, forming a record that cannot be changed without redoing the proof-of-work. The longest chain not only serves as proof of the sequence of events witnessed, but proof that it came from the largest pool of CPU power. As long as a majority of CPU power is controlled by nodes that are not cooperating to attack the network, they'll generate the longest chain and outpace attackers. The network itself requires minimal structure. Messages are broadcast on a best effort basis, and nodes can leave and rejoin the network at will, accepting the longest proof-of-work chain as proof of what happened while they were gone.

Bitcoin is introduced as a peer-to-peer electronic cash using digital signatures to trace transactions, which overcomes the double-spending problem without relying on a trusted third party. The double-spending problem is overcome using a hash-based proof-of-work system. Some of the main properties of the Bitcoin network are that:

Don't worry if this doesn't make sense to you at this stage, I recommend getting familiar with the following cryptographic and networking concepts, and then re-reading the abstract. Note proof-of-work is not introduced here since it is discussed at length later.

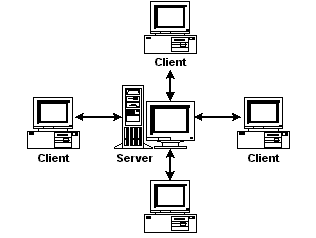

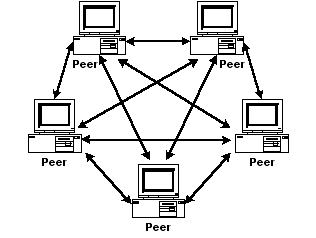

Peer-to-peer: a fundamental design feature of Bitcoin is that it is built as a peer-to-peer (P2P) network, as opposed to a client-server network. In a client-server architecture communication is usually to and from a central server providing resources. A P2P network is a distributed architecture, in which nodes are both consumers and suppliers of resources, removing the need for a centralised authority. In the case of Bitcoin a network designed for the transfer of value a centralised authority would be represented by a bank or financial institution. The use of P2P networks first became widely popular with music sharing applications such as Napster, and then through file sharing with BitTorrent.

client-to-server

peer-to-peer

Hashing: cryptographic hash functions are mathematical functions that can take any data and turn it into a fixed length output hash, where the same input data will reliably give the same output hash, if the data is even slightly modified then the hash will completely change. A hash function is a one way function, meaning if f is the hashing function, calculating f(x) is easy and fast, but trying to obtain x again is hard and infeasible due to the computational complexity. Hash functions are used, in digital signatures, message authentication codes, manipulation detection, fingerprints, checksums (message integrity check), hash tables, password storage and much more.

Hashes are large numbers, usually written in hexadecimal. Bitcoin uses secure hash algorithm 2 (SHA-256), which returns a 256 bit hash string (represented as hexadecimal below), here is an example of sha256 hashing in python:

In [1]: import hashlib

In [2]: hashlib.sha256(b"here is a bytestring to be hashed").hexdigest()

Out[2]: '7b02d50f844957522e4f1bb4514c0a76bd043eb87b290d43f21ca2508ea19e6b'

In [3]: hashlib.sha256(b"here is another bytestring to be hashed").hexdigest()

Out[3]: '1dbb72fc530b143d450fe3709c6c35d193fa8e1f6110acfdac6f2769f8eec7ce'

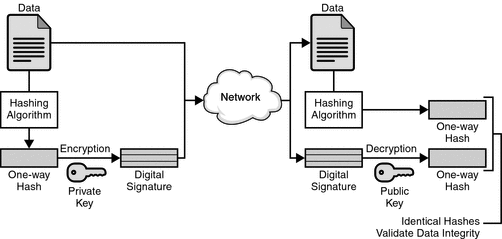

Digital signatures: a digital signature binds a person/entity to digital data, in a way that can be verified by a receiver or third party. This is analagous to signing a document by hand, which binds the signatory to a message. In order to have a purely digital replacement for physical paper signatures, each user must be able to produce a message whose authenticity can be checked by anyone, but which could not have been produced by anyone else. In Bitcoin digital signatures provide a way to ensure that all transactions are only made by the rightful owners of that coin.

Digital signatures are based on public key cryptography, a form of asymmetric cryptography. A public key algorithm such as RSA (Rivest–Shamir–Adleman) is commonly used, although Bitcoin and many cryptocurrencies use the more secure elliptic curve digital signature algorithm (ECDSA). In public key cryptography one can generate two keys that are mathematically linked, one private and one public. A digital signature is created by hashing a one-way hash of electronic data to be signed. The private key is then used to encrypt the hash. The encrypted hash along with extra information including the hashing algorithm is the digital signature. The hash is encrypted instead of the entire message since the hash is usually much shorter, saving time and computation.

Double-spending: The double-spending problem is a potential flaw in a digital monetary system in which the same token can be replicated and spent more than once, thereby causing inflation and destroying trust in the system. Double-spending exists in cash based financial systems as money counterfeiting, but with digital data it is potentially much easier to replicate and distribute money. A central authority can be used to overcome this problem and validate all transactions, but it is harder in a distributed system like Bitcoin. Bitcoin is the first successful distributed system that overcomes the double-spending problem.

Best effort basis: Best effort basis is an agreement that something will be attempted without any guarantee provided that it will succeed. In terms of a network best-effort delivery describes a network service in which the network does not provide any guarantee that data is delivered or that delivery meets any quality of service.

Further reading:

Commerce on the Internet has come to rely almost exclusively on financial institutions serving as trusted third parties to process electronic payments. While the system works well enough for most transactions, it still suffers from the inherent weaknesses of the trust based model. Completely non-reversible transactions are not really possible, since financial institutions cannot avoid mediating disputes. The cost of mediation increases transaction costs, limiting the minimum practical transaction size and cutting off the possibility for small casual transactions, and there is a broader cost in the loss of ability to make non-reversible payments for non-reversible services. With the possibility of reversal, the need for trust spreads. Merchants must be wary of their customers, hassling them for more information than they would otherwise need. A certain percentage of fraud is accepted as unavoidable. These costs and payment uncertainties can be avoided in person by using physical currency, but no mechanism exists to make payments over a communications channel without a trusted party.It is interesting to note that since publication in 2008 the original use case presented of Bitcoin has changed, due to constraints on the number of transactions the network can process. Transactions are throttled by the size and frequency of blocks in the blockchain. The original intention of Bitcoin was to facilitate low value non-reversible transactions, with the idea that the cost is reduced since no third party is required to mediate disputes. However, as the network has grown and the number of transactions has increased the fees to use network have also increased. This increase in fees makes small value transactions uneconomical. Engineers are now working on so called 'layer 2' solutions to the scalability problem such as the lightning network that take transactions off-chain, thus reducing transaction fees and congestion on the Bitcoin network.

What is needed is an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust, allowing any two willing parties to transact directly with each other without the need for a trusted third party. Transactions that are computationally impractical to reverse would protect sellers from fraud, and routine escrow mechanisms could easily be implemented to protect buyers. In this paper, we propose a solution to the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer distributed timestamp server to generate computational proof of the chronological order of transactions. The system is secure as long as honest nodes collectively control more CPU power than any cooperating group of attacker nodes.

Escrow mechanisms: An escrow is a contractual arrangement in which a third party receives and disburses money or documents for the primary transacting parties, with the disbursement dependent on conditions agreed to by the transacting parties, or an account established by a broker for holding funds on behalf of the broker's principal or some other person until the consummation or termination of a transaction. An escrow mechanism can be used for example to release funds once an item bought online has been received.

Further reading:

We define an electronic coin as a chain of digital signatures. Each owner transfers the coin to the next by digitally signing a hash of the previous transaction and the public key of the next owner and adding these to the end of the coin. A payee can verify the signatures to verify the chain of ownership.This section describes how Bitcoin are moved through the system using a sequence of transfers made with digital signatures. The history of each and every Bitcoin transaction leads back to the point where the bitcoins were first produced. Be aware that the transaction mechanism shown here is not the same as the concept of a blockchain, which is discussed later, but rather how money is traced and transferred through the network.The problem of course is the payee can't verify that one of the owners did not double-spend the coin. A common solution is to introduce a trusted central authority, or mint, that checks every transaction for double spending. After each transaction, the coin must be returned to the mint to issue a new coin, and only coins issued directly from the mint are trusted not to be double-spent. The problem with this solution is that the fate of the entire money system depends on the company running the mint, with every transaction having to go through them, just like a bank.

We need a way for the payee to know that the previous owners did not sign any earlier transactions. For our purposes, the earliest transaction is the one that counts, so we don't care about later attempts to double-spend. The only way to confirm the absence of a transaction is to be aware of all transactions. In the mint based model, the mint was aware of all transactions and decided which arrived first. To accomplish this without a trusted party, transactions must be publicly announced [1], and we need a system for participants to agree on a single history of the order in which they were received. The payee needs proof that at the time of each transaction, the majority of nodes agreed it was the first received.

The important part here is to understand the figure, showing how at each stage the owner is a person/entity holding the private key that gives them the ability to spend/transfer that money. When a transaction is broadcast other users can validate based on the public key of the signer, to ensure they have sufficient funds to make the transaction. This is facilitated by the asymmetry of the public-private key pair, whereby anyone can decrypt the signature and verify the transaction but only the owner can encrypt and sign to create another transaction. Although this is a useful way to keep track of ownership there is nothing to stop somebody spending their coins more than once, i.e. the double-spending problem.

The solution we propose begins with a timestamp server. A timestamp server works by taking a hash of a block of items to be timestamped and widely publishing the hash, such as in a newspaper or Usenet post [2, 3, 4, 5]. The timestamp proves that the data must have existed at the time, obviously, in order to get into the hash. Each timestamp includes the previous timestamp in its hash, forming a chain, with each additional timestamp reinforcing the ones before it.At this point Satoshi introduces the concept of a chain of timestamped blocks, also known as the blockchain. The first work on a cryptographically secured chain of blocks was described in 1991 by Stuart Haber and W. Scott Stornetta for time stamping digital documents. The idea here is to group transactions into blocks to verify that a transaction existed at a certain time, in this way we can overcome the double-spending problem by knowing whether coins have already been spent at a certain time, since these blocks are broadcast to the network, and the most recent block on the longest chain accepted as the current state of the ledger.

The gruesome analogy that comes to mind here is how a kidnapper might use a photo of their victim with that day's newspaper in order to authenticate that as of a certain date given by the publication of a newspaper the victim is still alive. Similarly by using a timestampped server we can authenticate that a transaction has been included in a block at a certain time and cannot be made again later. These blocks are the heartbeat of the network where information is assimilated on the ledger and a state agreed upon.

When you sign a transaction and broadcast to the network, it is not immediately assimilated into the blockchain. But depending on the transaction fee and load on the network it will be compiled into a block. As more blocks are added to the chain the transaction becomes ossified in the history, since it would require increasing proof-of-work to go back and change the record.

Usenet: An early peer-to-peer architecture mentioned in the Bitcoin paper is USENET, a distributed messaging system developed in 1979. Users read and post messages (called articles or posts, and collectively termed news) to one or more categories, known as newsgroups.

Further reading:

To implement a distributed timestamp server on a peer-to-peer basis, we will need to use a proof-of-work system similar to Adam Back's Hashcash [6], rather than newspaper or Usenet posts. The proof-of-work involves scanning for a value that when hashed, such as with SHA-256, the hash begins with a number of zero bits. The average work required is exponential in the number of zero bits required and can be verified by executing a single hash.The proof-of-work system is a kind of puzzle that miners on the network compete to solve first. Miners will first combine transactions into a block according to the rules of the network. They use the block header and a nonce value to to generate a hash, if the hash is less than a target value they win. This is done by randomly or pseudo-randomly changing a nonce value in the block until a hash is achieved with sufficient number of leading zeros. The more zeroes the more rare the hash is. A good hash' outcome is not predictable, and so you have to try a lot of times to find a good nonce. The amount of zeroes are based on how difficult it is supposed to be to find a block. In Bitcoin it adjusts to have a new block every 10 minutes (on average, given the rate at which previous blocks are found).

For our timestamp network, we implement the proof-of-work by incrementing a nonce in the block until a value is found that gives the block's hash the required zero bits. Once the CPU effort has been expended to make it satisfy the proof-of-work, the block cannot be changed without redoing the work. As later blocks are chained after it, the work to change the block would include redoing all the blocks after it.The proof-of-work also solves the problem of determining representation in majority decision making. If the majority were based on one-IP-address-one-vote, it could be subverted by anyone able to allocate many IPs. Proof-of-work is essentially one-CPU-one-vote. The majority decision is represented by the longest chain, which has the greatest proof-of-work effort invested in it. If a majority of CPU power is controlled by honest nodes, the honest chain will grow the fastest and outpace any competing chains. To modify a past block, an attacker would have to redo the proof-of-work of the block and all blocks after it and then catch up with and surpass the work of the honest nodes. We will show later that the probability of a slower attacker catching up diminishes exponentially as subsequent blocks are added.

To compensate for increasing hardware speed and varying interest in running nodes over time, the proof-of-work difficulty is determined by a moving average targeting an average number of blocks per hour. If they're generated too fast, the difficulty increases.

So for example the first hash ever found was the following, note the previous block is all zeros since there was no previous block!

Block 0

Hash 000000000019d6689c085ae165831e934ff763ae46a2a6c172b3f1b60a8ce26f

Previous Block 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

As you can see by block 100000, as more miners have joined the network the hashing power has increased, and the number of leading zeros in the hash to be found has increased from 10 at block 0 to 11 at block 100000. Adjusting the number of leading zeros is how the system regulates the blocktime.

Block 100000

Hash 000000000003ba27aa200b1cecaad478d2b00432346c3f1f3986da1afd33e506

Previous Block 000000000002d01c1fccc21636b607dfd930d31d01c3a62104612a1719011250

Again by block 500000 the difficult has increased again (more leading zeros).

Block 500000

Hash 00000000000000000024fb37364cbf81fd49cc2d51c09c75c35433c3a1945d04

Previous Block 0000000000000000007962066dcd6675830883516bcf40047d42740a85eb2919

When a miner finds a hash with enough leading zeros, you can think of it as them winning that competition. They can then propagate the block to the network and mint themselves some Bitcoin, if other miners agree that the block is valid they will start working to compile the next block... so the cycle continues.

This distributed proof-of-work system is how Bitcoin obtains consensus. In order to achieve this the system has to overcome the Byzantine General's Problem, a classic problem faced by any distributed computer system network. The Byzantine General's problem is explained through a scenario in which multiple divisions of an army are laying seige to a city. Each division has a general, that can communicate to other generals via a messenger. A majority have to agree to attack or to defend, but the difficulty arises since some of the generals or messengers may be untrustworthy.

A networked system is Byzantine Fault Tolerant if the system is dependable, where components may fail and there is imperfect information on whether a component is failed. So if one or more generals decide to go rogue and ignore the other generals then so long as they are not a majority the system will tolerate it. The bitcoin network works in parallel to generate a chain of Hashcash style proof-of-work. The proof-of-work chain is the key to overcome Byzantine failures and to reach a coherent global view of the system state. When a miner has done sufficient work to obtain a hash they are incentivised to obey the rules of the network and generate a valid block and claim their reward in Bitcoins. This overcomes the Byzantine General's problem since it becomes very expensive to become a bad actor and attack the network. It also makes it extremely computationally expensive to rewrite historical transactions on the network since the proof-of-work has to be done again for all blocks since the transaction.

Proof-of-work is not the only mechanism for achieving a consensus, other approaches such as proof-of-stake, and delegated proof-of-stake are being used. These are advantageous in their lower energy consumption. Attempts have also been made by cryptocurrencies like Primecoin which requires clients to find unknown prime numbers of certain types, which can have useful side-applications.

Hashcash: is a proof-of-work system used to limit email spam and denial-of-service attacks. The idea was to require that some computational work be done in order to send an e-mail, the receiver can then verify that work has been done. This would make it expensive to send spam e-mails to thousands of addresses.

Further reading:

The steps to run the network are as follows:Nodes always consider the longest chain to be the correct one and will keep working on extending it. If two nodes broadcast different versions of the next block simultaneously, some nodes may receive one or the other first. In that case, they work on the first one they received, but save the other branch in case it becomes longer. The tie will be broken when the next proof-of-work is found and one branch becomes longer; the nodes that were working on the other branch will then switch to the longer one.

- New transactions are broadcast to all nodes.

- Each node collects new transactions into a block.

- Each node works on finding a difficult proof-of-work for its block.

- When a node finds a proof-of-work, it broadcasts the block to all nodes.

- Nodes accept the block only if all transactions in it are valid and not already spent.

- Nodes express their acceptance of the block by working on creating the next block in the chain, using the hash of the accepted block as the previous hash.

New transaction broadcasts do not necessarily need to reach all nodes. As long as they reach many nodes, they will get into a block before long. Block broadcasts are also tolerant of dropped messages. If a node does not receive a block, it will request it when it receives the next block and realizes it missed one.

For a bit of clarity any computer that connects to the Bitcoin network is called a node. Nodes that fully verify all of the rules of Bitcoin are called full nodes. Full nodes in the Bitcoin network have a complete copy of the blockchain and are able to verify all transactions since the genesis block at the start of the network. Basically, the miner works on transactions by coming up with the best combination to store that information. Miners spend about 10 minutes working on a problem, but nodes keep that result forever after in the database and verify it with others. Miners don't need to know about prior blocks (except for the prior one) with very few exceptions.

Further reading:

By convention, the first transaction in a block is a special transaction that starts a new coin owned by the creator of the block. This adds an incentive for nodes to support the network, and provides a way to initially distribute coins into circulation, since there is no central authority to issue them. The steady addition of a constant of amount of new coins is analogous to gold miners expending resources to add gold to circulation. In our case, it is CPU time and electricity that is expended.

The incentive can also be funded with transaction fees. If the output value of a transaction is less than its input value, the difference is a transaction fee that is added to the incentive value of the block containing the transaction. Once a predetermined number of coins have entered circulation, the incentive can transition entirely to transaction fees and be completely inflation free.

The incentive may help encourage nodes to stay honest. If a greedy attacker is able to assemble more CPU power than all the honest nodes, he would have to choose between using it to defraud people by stealing back his payments, or using it to generate new coins. He ought to find it more profitable to play by the rules, such rules that favour him with more new coins than everyone else combined, than to undermine the system and the validity of his own wealth.

The total number of Bitcoins that can be mined is slightly less than 21 million, with the rate at which Bitcoins can be mined reducing over time. This reduction happens in halving events, where approximately every 4 years the number of Bitcoins mined in each block reduces from 50 Bitcoin per block, to 25 Bitcoin, to 12.5 Bitcoin etc. This leads to a deflationary currency, since the rate of increase in supply is reducing over time and will reach a stable number of coins around the year 2140. When miners can no longer mine new Bitcoins the network will sustain only on transaction fees alone.

Further reading:

Once the latest transaction in a coin is buried under enough blocks, the spent transactions before it can be discarded to save disk space. To facilitate this without breaking the block's hash, transactions are hashed in a Merkle Tree [7, 2, 5], with only the root included in the block's hash. Old blocks can then be compacted by stubbing off branches of the tree. The interior hashes do not need to be stored.A block header with no transactions would be about 80 bytes. If we suppose blocks are generated every 10 minutes, 80 bytes * 6 * 24 * 365 = 4.2MB per year. With computer systems typically selling with 2GB of RAM as of 2008, and Moore's Law predicting current growth of 1.2GB per year, storage should not be a problem even if the block headers must be kept in memory.

Merkle Tree: a Merkle tree is a hash-based data structure that is a generalisation of the hash list. It is a tree structure in which each leaf node is a hash of a block of data, and each non-leaf node is a hash of its children. Typically, Merkle trees have a branching factor of 2, meaning that each node has up to 2 children. Hash trees can be used to verify any kind of data stored, handled and transferred in and between computers. They can help ensure that data blocks received from other peers in a peer-to-peer network are received undamaged and unaltered, and even to check that the other peers do not lie and send fake blocks.

Further reading:

Once the latest transaction in a coin is buried under enough blocks, the spent transactions before it can be discarded to save disk space. To facilitate this without breaking the block's hash, transactions are hashed in a Merkle Tree [7, 2, 5], with only the root included in the block's hash. Old blocks can then be compacted by stubbing off branches of the tree. The interior hashes do not need to be stored.As such, the verification is reliable as long as honest nodes control the network, but is more vulnerable if the network is overpowered by an attacker. While network nodes can verify transactions for themselves, the simplified method can be fooled by an attacker's fabricated transactions for as long as the attacker can continue to overpower the network. One strategy to protect against this would be to accept alerts from network nodes when they detect an invalid block, prompting the user's software to download the full block and alerted transactions to confirm the inconsistency. Businesses that receive frequent payments will probably still want to run their own nodes for more independent security and quicker verification.

A block header with no transactions would be about 80 bytes. If we suppose blocks are generated every 10 minutes, 80 bytes * 6 * 24 * 365 = 4.2MB per year. With computer systems typically selling with 2GB of RAM as of 2008, and Moore's Law predicting current growth of 1.2GB per year, storage should not be a problem even if the block headers must be kept in memory.

Simplified payment verification is a method for verifying if particular transactions are included in a block without downloading the entire block. The method is used by some lightweight Bitcoin clients. The simplified verification verification client only needs download the block headers, which are much smaller than the full blocks. To verify that a transaction is in a block, a simplified verification client requests a proof of inclusion, in the form of a Merkle branch.

Further reading:

Although it would be possible to handle coins individually, it would be unwieldy to make a separate transaction for every cent in a transfer. To allow value to be split and combined, transactions contain multiple inputs and outputs. Normally there will be either a single input from a larger previous transaction or multiple inputs combining smaller amounts, and at most two outputs: one for the payment, and one returning the change, if any, back to the sender.It should be noted that fan-out, where a transaction depends on several transactions, and those transactions depend on many more, is not a problem here. There is never the need to extract a complete standalone copy of a transaction's history.

Further reading:

The traditional banking model achieves a level of privacy by limiting access to information to the parties involved and the trusted third party. The necessity to announce all transactions publicly precludes this method, but privacy can still be maintained by breaking the flow of information in another place: by keeping public keys anonymous. The public can see that someone is sending an amount to someone else, but without information linking the transaction to anyone. This is similar to the level of information released by stock exchanges, where the time and size of individual trades, the "tape", is made public, but without telling who the parties were.Bitcoin is often perceived as an anonymous payment network, but in actuality it is very transparent since all transactions are visible, but the identity of the address owners is not known. By combining transactions and through analysing groups of transactions the anonymity of Bitcoin can be compromised. Other cryptocurrencies such as Monero, and Zcash attempt to provide a more anonymous payment method, but at the expense of increased computation.As an additional firewall, a new key pair should be used for each transaction to keep them from being linked to a common owner. Some linking is still unavoidable with multi-input transactions, which necessarily reveal that their inputs were owned by the same owner. The risk is that if the owner of a key is revealed, linking could reveal other transactions that belonged to the same owner.

Further reading:

We consider the scenario of an attacker trying to generate an alternate chain faster than the honest chain. Even if this is accomplished, it does not throw the system open to arbitrary changes, such as creating value out of thin air or taking money that never belonged to the attacker. Nodes are not going to accept an invalid transaction as payment, and honest nodes will never accept a block containing them. An attacker can only try to change one of his own transactions to take back money he recently spent.

The race between the honest chain and an attacker chain can be characterized as a Binomial Random Walk. The success event is the honest chain being extended by one block, increasing its lead by +1, and the failure event is the attacker's chain being extended by one block, reducing the gap by -1. The probability of an attacker catching up from a given deficit is analogous to a Gambler's Ruin problem. Suppose a gambler with unlimited credit starts at a deficit and plays potentially an infinite number of trials to try to reach breakeven. We can calculate the probability he ever reaches breakeven, or that an attacker ever catches up with the honest chain, as follows [8]:

p = probability an honest node finds the next block

q = probability the attacker finds the next block

qz = probability the attacker will ever catch up from z blocks behindGiven our assumption that p > q, the probability drops exponentially as the number of blocks the attacker has to catch up with increases. With the odds against him, if he doesn't make a lucky lunge forward early on, his chances become vanishingly small as he falls further behind.

We now consider how long the recipient of a new transaction needs to wait before being sufficiently certain the sender can't change the transaction. We assume the sender is an attacker who wants to make the recipient believe he paid him for a while, then switch it to pay back to himself after some time has passed. The receiver will be alerted when that happens, but the sender hopes it will be too late.

The receiver generates a new key pair and gives the public key to the sender shortly before signing. This prevents the sender from preparing a chain of blocks ahead of time by working on it continuously until he is lucky enough to get far enough ahead, then executing the transaction at that moment. Once the transaction is sent, the dishonest sender starts working in secret on a parallel chain containing an alternate version of his transaction.

The recipient waits until the transaction has been added to a block and z blocks have been linked after it. He doesn't know the exact amount of progress the attacker has made, but assuming the honest blocks took the average expected time per block, the attacker's potential progress will be a Poisson distribution with expected value:To get the probability the attacker could still catch up now, we multiply the Poisson density for each amount of progress he could have made by the probability he could catch up from that point:

Rearranging to avoid summing the infinite tail of the distribution...

Converting to C code...

include math.h double AttackerSuccessProbability(double q, int z) { double p = 1.0 - q; double lambda = z * (q / p); double sum = 1.0; int i, k; for (k = 0; k <= z; k++) { double poisson = exp(-lambda); for (i = 1; i <= k; i++) poisson *= lambda / i; sum -= poisson * (1 - pow(q / p, z - k)); } return sum; }Running some results, we can see the probability drop off exponentially with z.

q=0.1 z=0 P=1.0000000 z=1 P=0.2045873 z=2 P=0.0509779 z=3 P=0.0131722 z=4 P=0.0034552 z=5 P=0.0009137 z=6 P=0.0002428 z=7 P=0.0000647 z=8 P=0.0000173 z=9 P=0.0000046 z=10 P=0.0000012 q=0.3 z=0 P=1.0000000 z=5 P=0.1773523 z=10 P=0.0416605 z=15 P=0.0101008 z=20 P=0.0024804 z=25 P=0.0006132 z=30 P=0.0001522 z=35 P=0.0000379 z=40 P=0.0000095 z=45 P=0.0000024 z=50 P=0.0000006Solving for P less than 0.1%...

P less than 0.001 q=0.10 z=5 q=0.15 z=8 q=0.20 z=11 q=0.25 z=15 q=0.30 z=24 q=0.35 z=41 q=0.40 z=89 q=0.45 z=340

Further reading:

We have proposed a system for electronic transactions without relying on trust. We started with the usual framework of coins made from digital signatures, which provides strong control of ownership, but is incomplete without a way to prevent double-spending. To solve this, we proposed a peer-to-peer network using proof-of-work to record a public history of transactions that quickly becomes computationally impractical for an attacker to change if honest nodes control a majority of CPU power. The network is robust in its unstructured simplicity. Nodes work all at once with little coordination. They do not need to be identified, since messages are not routed to any particular place and only need to be delivered on a best effort basis. Nodes can leave and rejoin the network at will, accepting the proof-of-work chain as proof of what happened while they were gone. They vote with their CPU power, expressing their acceptance of valid blocks by working on extending them and rejecting invalid blocks by refusing to work on them. Any needed rules and incentives can be enforced with this consensus mechanism.Et voila! This paper did not cause much of a stir on release, but Satoshi worked to build a minimum implementation. At a couple of points in its early history the Bitcoin project was almost completely abandoned. However, over time a core team of devoted developers emerged and the Bitcoin protocol and ecosystem has flourished since, opening a pandora's box of innovation in distributed transfer of value over the internet.

Since the release of this paper the network has evolved and adapted, in ways that would have been difficult to predict in 2008. Due to the incentives in mining and how potentially lucrative it is mining has gone from being done on CPUs, to more parallelisable GPUs. Then companies started designing custom Application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) chips. That is to say chips especially designed to perform the proof-of-work required by Bitcoin. Developments in ASIC technology are highly secretive and very competitive. Meaning that for a single user to start mining on their PC it is no longer profitable. Large companies have gained significant mining power in the network, mainly operating in countries or places like China with subsidised electricity and cheap hardware. Another change has been the development of mining pools where users can group together and donate their computational resources in return for some fraction of mining reward. Both of these developments in large mining companies and mining pools have lead to increasing centralisation of the netwok.

Bitcoin has also deviated from the original vision of the paper in the fact that its use as a means of payment for low value goods is becoming rarer. That is to say it is increasingly being thought of as a kind of digital gold asset rather than an electronic cash, this is due to the high transaction fees and price volatility. However, as mentioned before additional protocol layers are being built on top of the Bitcoin network in the hope that it can again be used as a kind of electronic cash.

Despite these challenges, and plenty of drama along the way, this remarkable peer-to-peer electronic money continues to evolve and ten years later is still going strong!

Further reading:

It is interesting to note the pioneering Nick Szabo's work on systems such as bit gold is not referenced here ;-)[1] W. Dai, "b-money," http://www.weidai.com/bmoney.txt, 1998.

[2] H. Massias, X.S. Avila, and J.-J. Quisquater, "Design of a secure timestamping service with minimal trust requirements," In 20th Symposium on Information Theory in the Benelux, May 1999.

[3] S. Haber, W.S. Stornetta, "How to time-stamp a digital document,." In Journal of Cryptology, vol 3, no2, pages 99-111, 1991.

[4] D. Bayer, S. Haber, W.S. Stornetta, "Improving the efficiency and reliability of digital time-stamping," In Sequences II: Methods in Communication, Security and Computer Science, pages 329-334, 1993.

[5] S. Haber, W.S. Stornetta, "Secure names for bit-strings," In Proceedings of the 4th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, pages 28-35, April 1997.

[6] A. Back, "Hashcash - a denial of service counter-measure," http://www.hashcash.org/papers/hashcash.pdf, 2002.

[7] R.C. Merkle, "Protocols for public key cryptosystems," In Proc. 1980 Symposium on Security and Privacy, IEEE Computer Society, pages 122-133, April 1980.

[8] W. Feller, "An introduction to probability theory and its applications," 1957.

Finally, if you are looking for a more indepth explanation of Bitcoin I highly recommend Andreas Antonopoulos' book "Mastering Bitcoin".